East Side Games Group’s Josh Nilson on Changing the Game for Indigenous and Underrepresented Talent

Jason McRobbie

Group co-founder and GM Josh Nilson had his career choices laid out for him early on in a small, Northern BC town. ”They didn’t include becoming a game designer, a sought after speaker or winning countless gaming and business accolades”. Since climbing to the top of the game though—from an indie, gaming studio in 2011 to being acquired for $159 million in February 2021 and now trading on the TSX as part of the East Side Games Group (TSX:EAGR-T)—Josh has taken a deeper look at the challenges of the co-lonial workplace. We sit down with Josh to talk about what is holding Indigenous and underrepresented talent back—and what leaders need to be doing to bring those colo-nial barriers down and people to thrive.

Key Takeaways:

- If leaders want to attract and grow Indigenous and other underrepresented talent pools, they need to commit to the work of decolonizing the workspace.

- Leaders need to better identify and live their brand in-office, online and in the broad-er community to reach and support those underrepresented demographics.

- Leaders need to look beyond traditional skillsets and degrees to find the value just beneath the surface within those seeking to move into tech from different fields.

His story is one with the power to change the game for many.

Though born Metis in Willow River, BC and passing through Lheidli T'enneh Nation land on his way to work, Josh Nilson, co-founder and GM of the Vancouver-based East Side Games Group, admits that he identified more with the culture of games than his own Indigenous roots.

“I’m not an expert at any of this, but Indigenous talent is something we’ve talked about for a long time and I realize my privilege and that opportunity that comes with it to help push things forward,” said Josh, pointing out the colonial trappings of the word Indigenous itself. “What we’re really talking about are a bunch of unique cultures, so I don’t speak on behalf of anyone but myself. After all, these are my own thoughts and feelings and I’m always changing. I realized though, I hadn't spoke up or told my story— so like it or not, this is my story.”

Caveat aside, Josh’s story and wisdoms resonate in an industry that thrives on digital dreams—and untapped talent.

“We were GenX, so we were the first wave that embraced playing video games. We played on the early consoles—I had the Intellivision—and dreamt of designing video games, while we designed levels and games in D&D,” said Josh. “Then the early computers came out that could plug into your TV as monitor and Texas Instruments made that dream to build more real than ever.”

For Josh, the future was clear. He wanted to design games. Unfortunately, his own tech dreams had the plug pulled early, despite a natural affinity and passion to learn more.

“I grew up in a really small town and we were pretty much taught that if we weren’t going to university, then we weren’t going to be doing these complex jobs,” said Josh. “The school I went to also serviced the country kids and we were all put in the same bucket—people who didn’t have the financial means to do stuff. There was no hope, no scholarships, no real choices. They said to me, ‘There’s no way you’ll be able to do this,’ and sort of pushed me away.”

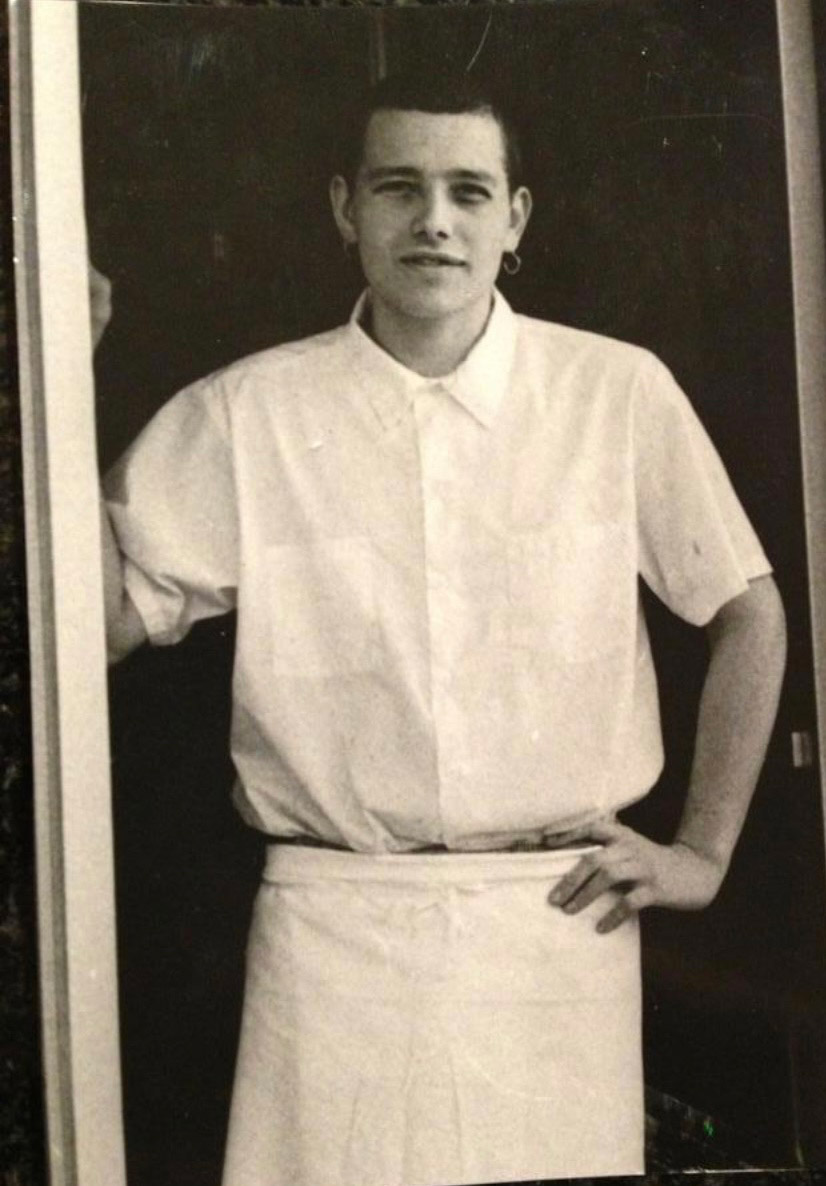

That push led Josh into kitchens for the next 15 years, where he built teams to run the busiest shifts, developed an appreciation for hardworking, undervalued brigades, and, ultimately, to where he is today. That said, before taking an IT course at Capilano University in 2001, while working two kitchens, he hadn’t even thought of a career designing games in the intervening years.

That course changed everything except for his kitchen ethos.

“Working in the kitchen and running a brigade is kind of the same thing as what we do with games. I’ve kind of had that same ethos throughout my career. Running a brigade and challenging them to be the best, managing people while making sure restaurants remain profitable, working super long hours—I will always respect that and I try to bring that into the products we make and people I talk to,” said Josh. “I think it resonates. The kitchen was my university—being able to learn that blue collar upbringing brings value.”

Moreover, being able to perceive the true value of that blue collar has been crucial to the team and brand building of the East Side Games Group—and a critical step in addressing the disparity in numbers that continues to plague Indigenous talent.

“I’ve been on a number of panels talking about this and gaming in particular. If you look at the TAP Network’s last talent survey, in games only 1.4 percent across all of BC identified as Indigenous, while based on population that should be closer to six or eight percent. We started asking ourselves at these meetings, ‘Why are we so behind?”

Nonetheless, Josh remains positive, pointing out that the figure had been 0.7 percent in the prior TAP Network survey, a progression marked not by an actual influx of Indigenous talent, but perhaps something even more valuable—a growing trust accompanying genuine efforts to decolonize the workspace.

“I don’t think decolonizing our workspace is only to do with focusing on Indigenous people, but looking at what that means as a company, even our own. From who we are and how we go to university to the ways we do business—this is all colonial stuff brought to us by colonial systems,” said Josh. “It’s been great that people are talking about it now and we have a lot of amazing speakers. Companies like Section35 have started designing clothing around the concept of decolonizing our workspace and they have a great exhibit at the Vancouver Art Gallery right now.”

However, while a greater believer in tech being the great equalizer—a phrase modded from a hero of his, Former Minister of Advanced Education, Skills and Training of BC Melanie Mark who put the original emphasis on education—Josh sees ample opportunity for companies to make their workspaces more accessible to Indigenous talent.

“When we’re looking at hiring and decolonizing our workspace, our work is never done, but we’re getting started. I think the first question we should be asking is, ‘Why don’t we have workspaces—including a lot of these progressive companies winning awards at the forefront—where people are comfortable identifying and giving that information at work?” asked Josh. “What it means for you as an organization is constant learning and retraining, which is hard work without any immediate ROI. As a leader of an organization though, what you need ask is, ‘How are you making it a better place for Indigenous people to work?’ And really, it’s not just a better place for Indigenous people, but for everyone to work.”

“So that is really the focus, ‘How do we make Indigenous people feel comfortable giving information in a workplace environment so we can improve across the entire spectrum?” asked Josh. “That unpacks other challenges—like what do we actually know about Indigenous peoples? What are we doing in these areas as an organization that is intentional or unintentional—and I like to think most of it is unintentional—that are making people feel uncomfortable. “

As proven by East Side Games, there are greater riches ranking higher than immediate ROI. As to how to garner those, Josh may very well have helped develop the new rules of the game:

Know who you are as a company and stand by it. “I don’t think there’s a way anymore, especially if you are starting a new company, that you can just go in and vanilla it up with ‘We believe in everything.’ I think you have to make a stand sometimes. If you want to make an inclusive space, you have to look at what doesn’t make an inclusive space and be able to push or keep that out.

We have right on our website—and it has cost us some business—that at East Side Games, we are not tolerant insofar as 'we do not tolerate the intolerant and we refuse to include the exclusive.’ If your free speech includes hate speech, we don’t have a job for you. I think it’s important to make a stand about that.

It’s about what you make in your company too. Our brand shines in our games (which range from RuPaul’s Drag Race Superstar to Star Trek: Lower Decks to their original breakout hit with Trailer Park Boys: Greasy Money). You have to really decide who you are, what you put on your website, whatever it is that you sell and how it will resonate with people. Will it make them happy? We’re constantly learning as a company.

Create a workspace culture that allows people to be themselves—even on holiday. Letting people choose what stat holidays they want is a great step to make. Jeff Ward from Animikii posted an awesome article about this the other day. His whole thing is giving people that choice. I think if you are going to be a diverse organization, you should have a similar mechanism in place so that people don’t have to for the most part just take what are white man holidays.

And if your company IS going to celebrate Canada Day and this issue is important to your culture, why are you not celebrating National Day for Truth and Reconciliation or Indigenous Peoples’ History Month or Indigenous Peoples’ Day? We should have an environment where people are comfortable asking these questions.

At East Side Games, we have a new flex-time off policy around holidays that are special to each employee. You can take that time off. You just have to make sure everyone knows. Or maybe you need a couple days to go off and learn something. You can do that.

Support your company values in the community to uplift talent. If you’re looking to get Indigenous or BIPOC talent or more women tech, look at what are you doing in order to make sure that five years from now you’ve made some progress.

We were doing the same thing as everyone else—sharing articles and not doing anything. So, together with Blackbird Interactive and Timbre Games Studio, we put forward an Indigenous person scholarship and through the Vancouver Film School we helped create a Women in Games scholarship—we really started sponsoring some grassroots talent. BC Tech has a program Digital Lift that gets marginalized people into tech to be retrained and we’ve been hiring from that program too.

We’ve also made big, small steps forward by supporting organizations in a way that we can learn—organizations like ImagineNative or the Vancouver Asian Film Festival—just so we can learn more about these cultures that we work with. I think a lot of companies overlook that. More companies should look at exploring sponsorship and getting involved from your C-level to your frontline to show your team who you support.

Learn to see degrees of value instead of only the value of degrees. “The reason I have such an issue with accreditation is because people who didn’t get into tech 10 years ago, but went to work on the pipelines or in forestry, now have 10 years’ experience working with teams on complex machines on complex jobs. You can’t tell me that their jobs are easier to do than managing people or learning to be AWS-certified and work on our servers or as an analyst or a producer. If you can learn to be a foreman, you can be trained to be a producer.

Of course, you’re always going to be looking for senior talent, but everyone has been saying that for ages—nothing has changed. But, if 10 or 20 years ago we had started cultivating junior talent, removed unnecessary education requirements from jobs that don’t require university training and started training on the job—all this great stuff that we’re seeing come with universities like Jelly Academy working on more of a ticketing system to get people in—then there wouldn’t be this issue.”

Commit to lifelong learning with no end but improvement: I think the biggest challenge, through the tech lens, the biggest pushback you get constantly is excuses on why companies can’t hire X talent, but it really comes down to not wanting to do the work - and it’s a lot of work. It means training for your executive team and your managers and paying people properly to come in and do that training with all its components. And you have to make it a yearly thing, much like you do with performance reviews, and to have a really solid plan around reaching that talent.

Most importantly, Josh stresses, just take that first step.

“I’ve learned that it is a lifelong learning to be Metis, so there is no being done,” said Josh, making no claim to paragon status. “We weren’t doing everything we could either and as a Metis man I should have stepped up and said something, but I didn’t and I’ve been thinking a lot about that.”

With words of humility well worth following, Josh has stepped into action and encourages other leaders to do the same for the sake of better business.

“Why care? You care if you are a leader in this industry because it is good for business and it is going to be essential. This is the time you have to do this and have to care in your business because the talent that is coming in—the brigade—they care about this stuff and they want to know what your plan is,” said Josh. “Salaries are just one lever. People also want to know your culture. THIS is your culture. Your culture is not your foozball table or your shirts. This is the DNA of your company and this is the lens that everyone should be using for the decisions that they make.”

BACK